After the sister’s death, there was nothing to report. The increased accidents in the park have either kept people away or kept them careful. All trails that lead to the Eye were closed to the public.

The weather was calm, so most days have been spent at the office drinking bad coffee and making sure everything was up to code. An occasional family member asked for information, but that was the only thing that caused any stress. However, right before the end of the day, we got a call.

Some descending mountaineers called about someone looking disoriented on the glacier. From what they saw, there was a man walking back and forth along the ridge of the Eye. Sunset was only a couple hours away, and he was alone. The only other details the reporters could provide was that the man was dressed in a red Marlboro ski suit.

The sky was clear but the wind was treacherous. We had no choice but to get back on our snowmobiles. Caitlin, Buck, David, and I all set off and arrived at the glacier only forty-five minutes after the call. At the base we decided against roping up. We knew the route up and it would be faster if we charged up with our ice axes as fast as we could.

None of us spoke as we made our way up. We couldn’t have even if we wanted to. Waves of wind crashed down on us. The pain of such a quick assent was only matched by the anxiety of knowing another person was there after the area was closed off. Whoever was there was there for a reason.

Visibility was low. Our goggles were frosted by the ripples of snow breaking off the ground, but we certain of our path. We knew where the Eye was by heart.

Of all the times I’ve spent in the wild, each summit had forms I’d never seen before. New ways the light graced the snow. Each crack in the rocks felt alive. It was always a new land, but the land around the Eye knew us. I was forgetting the details that disappear once you get comfortable.

“There he is!” Buck yelled.

All four of us lined up, looking at the man stumbling across the ridge of the Eye. He was hard to make out, but the reporters were right. He was dressed in a Marlboro ski outfit. A rope attached at his hip whipped around from the wind. We were maybe fifty feet away, and he hadn’t shown any sign that he noticed us.

“Hey son!” Buck yelled, “It’s getting late. You shouldn’t be up here!”

He said nothing and continued to walk.

“He seems off,” I said.

“I’ll go talk to him,” David said.

“I don’t know,” Caitlin said, “I don’t like this.”

“I don’t either,” David said, “but we gotta deal with him somehow. Kid, come with me.”

I looked to Buck and Caitlin, who both nodded in return.

“Lets circle him,” Caitlin said, “He’s going to the left, so Buck and I will stay low while you two approach.”

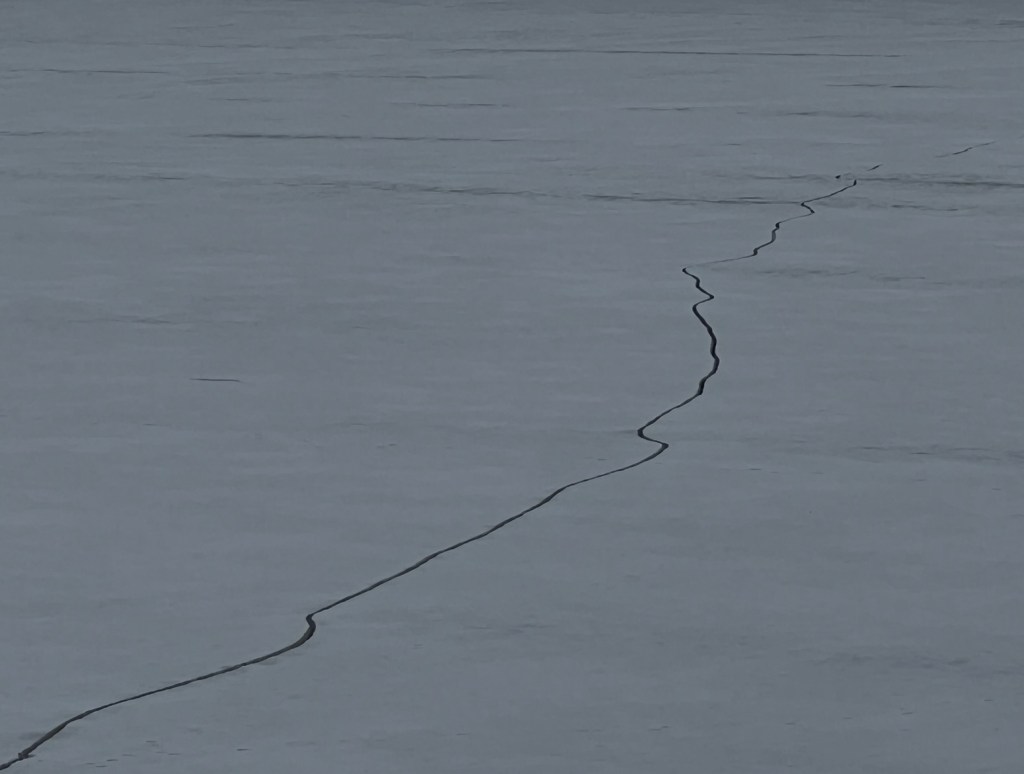

David and I nodded and started walking. Twenty feet away and he took no notice of us. The wind kept blurring our goggles, but we could still make out his silhouette against the snow. His support rope dangled behind him. Ten feet away and standing at the ridge of the Eye, David stopped to point at the rope.

“Grab it if he does anything.”

I kneeled in the snow, waiting next to the rope as I watched David approach.

As I watched the man walk away from us, I noticed that his suit was frozen solid. Each ripple in the fabric reflected a different shade of setting sun. As David got closer, he ignored us. He looked stiff, yet calm.

David, his shoulders back, walked just a few feet behind him and yelled, “Turn around!”

The man continued to walk. David took a few steps forward.

“Can you hear me?” he screamed.

By now, the mean had reached the edge of where one curve of the Eye met the other. As if he was moving on a track, he turned around to trace his steps back towards us.

David stood still, but after seeing the man’s face, I don’t know how.

Broken, rotten skin, held on just enough to show the curves of the man’s skull beneath his hood. His nose was gone, burned off by hypothermia. Only two black holes were left beneath the ski goggles frozen to his face. His lips had shriveled back into his face, and against the black cracks of frozen flesh and the lines of ruined veins, his teeth were a flawless white.

David pulled his ice axe behind his back, ready to swing. The man kept walking forward with his indifferent skeletal grin.

“Go back, kid,” he yelled at me, “Now!”

I watched as David lunged forward and slammed his axe into the side of the man’s skull. His head whipped to the side and his goggles flew down towards Buck and Caitlin who were now sprinting up the hill.

David recoiled expecting a strike, but none came. The man simply turned around and walked away.

I watched as his support rope followed him and without hesitation, I grabbed it to stop his escape. I plunged my gloves into the snow and gripped the rope tight. The rope, however, slid through my hands, and where I expected the sound of fiction, I heard only a gush of liquid. I looked closer at the rope and screamed.

“This isn’t a rope!”

When I looked up at David, I saw him thrown down the side of the mountain as the man pushed him. He locked onto me in a dead sprint. His jaw was open wide as if he were screaming, but there was nothing but the rasp of air passing through his mouth getting louder as he got closer.

I was frozen in fear as he lunged at my hands like an animal. Just before he hit me, I let go, and I was thrown down into the Eye.

My crampons dug into the ice but it was slick. As I fumbled for my axe, I was slipping closer to the hole like I was being sucked inside a drain. I self arrested, throwing my weight onto the axe as hard as I could. Just at the edge, it cut into the ice and I stopped with only inches between me and the pit.

I looked up at the ridge to see the man continuing his walk as if nothing had happened. As he walked away, I watched the rope ripple as it dangled at my side, leading right into the hole next to me.

Just as he walked in front of the sun, he came to a stop as part of the back of his neck ripped out. Blood flicked against the ice. I gasped. I saw Caitlin appear from behind him, and just as I realized what she had done, she ripped her axe back out from his neck.

The man stood only for a brief moment before crumbling to the ground. Some of his blood seeped from his neck onto the ice, flowing down towards me. I watched it drip into the hole, and for a moment, I peered inside to see where it would fall.

I quickly took my head out of the hole. I saw nothing, but I was shocked by the sound coming from the pit. There was no echo, no point where sound reflected space. It was like when a car passes under a bridge during a storm and for a fleeting moment, the pounding stops and you can only hear the emptiness in-between.

My name ripped through the air as soon as my ears crossed the threshold back into the air. Buck was yelling for me to grab a rope he’d thrown to me.

When they hauled me out, everyone gathered around me to see if I was okay. Buck gave me a suffocating hug while Caitlin placed her hand on my head.

“Where’s David?” I said.

We turned to see David standing over the man’s corpse.

“You should stay here,” Buck said to me.

“No, it’s alright. I’m okay, really.”

They both helped me up and we walked towards David, who was now kneeling at the man’s side.

When he grabbed the dead man’s rope, I froze, but he didn’t move.

In the stillness, the rope appeared no longer artificial but as a dark colored flesh, shimmering faintly against the light.

David softly followed the rope towards the man’s belt with his hand. At the dead man’s hips, he paused. After giving us a blank look, he continued following the rope under his clothes. David pulled up the man’s jacket, then his shirt, to reveal the rope attached at his stomach.

Everyone was silent as they looked at the body. Buck’s hand tightened against my arm. I could tell we were all taking in the same image our minds would try and force us to forget. In the back of my mind, the bodies I’ve found at this job tend to console the others. They don’t seem so bad after a while, but despite the grotesque sight of his waist, what I remember about this one were his eyes. His soft brown eyes were in perfect condition, staring blankly at the empty sky.

Without saying a word, David took his pocket knife out and cut the cord from the man’s body. Rotten blood poured out, pulsing across the man’s now undulating stomach. He twitched for just a moment, only to rest again the next.

The rope slowly slipped back into the Eye and the blood left behind followed.

After that, the helicopter blades couldn’t cut the silence. The pilot asked us about the body and why we decided to leave it, and we said nothing. I leaned into the window to watch the sunset refract through frozen tears.

For the last time, I watched as the sun set on my escape, only now through eyes I wished had never been opened.