Out of a passion for internet history and to get some much needed inspiration, I decided to peruse some old blogs. I put some of my own writing aside for the sake of sharing this one that I retrieved from the Internet Archive. It was published in the winter of 2001. I’ve taken the liberty of changing some real names to simple placeholders and cleaned up some grammatical errors (I may have missed some). I will post more entries as I continue to put them together. They are scattered, but I’ve taken to calling them “Our Place in the Ice.”

Entry #1

If we don’t know, we cannot react. If we can’t react, we cannot hope. When I discuss what I’ve seen with others, they dismiss the patterns and gesture at the great unknown to explain it all away. I’ve seen too much for the charity that comes with accepting the emptiness of it all. There is a path through the unexplainable, either towards understanding itself or the true limits. Fighting to know either one of them is terrifying. A life in the wild has required that I learn this.

I’ve been volunteering with the local rescue team for almost four years since I moved to Alaska. I’ve come to accept the necessary grit I need to push myself into the mountains, but also the compassion to hold my boundary with the earth. I’ve broken through too much snow to find it’s turned red, to witness an adventurer on their final date with nature. The one that’s always coming, and yet it’s the one they never expect. The piece of equipment most commonly left behind by the people we rescue is humility.

I was eighteen when I started. Since I was thirteen I was climbing at any place my bike could take me. I solo camped in the winter and read about survival skills by flashlight. When I was sixteen, I took my car and I soloed the mountaineer’s route at Mount Whitney. I told my PE teacher about it and my mom got a call from the school.

A welfare check. My greatest honor. She didn’t care, lucky for me. I took off from home and high school as soon as the law would let me.

I got a job in a lumberyard and pestered my way into being involved in the local rescue team. Observing, then record keeping, then carrying the gear. For the past year, I’ve been saving lives. Consistently too, which is what has made recent events so strange.

On Friday, September 20th, we got a call from some hikers about a skier who crashed into a crevasse. The afternoon weather was clear so we took the helicopter and confirmed it from above: half of a broken ski laying towards the bottom of a crevasse less than a quarter mile where the glacier met the mountainside.

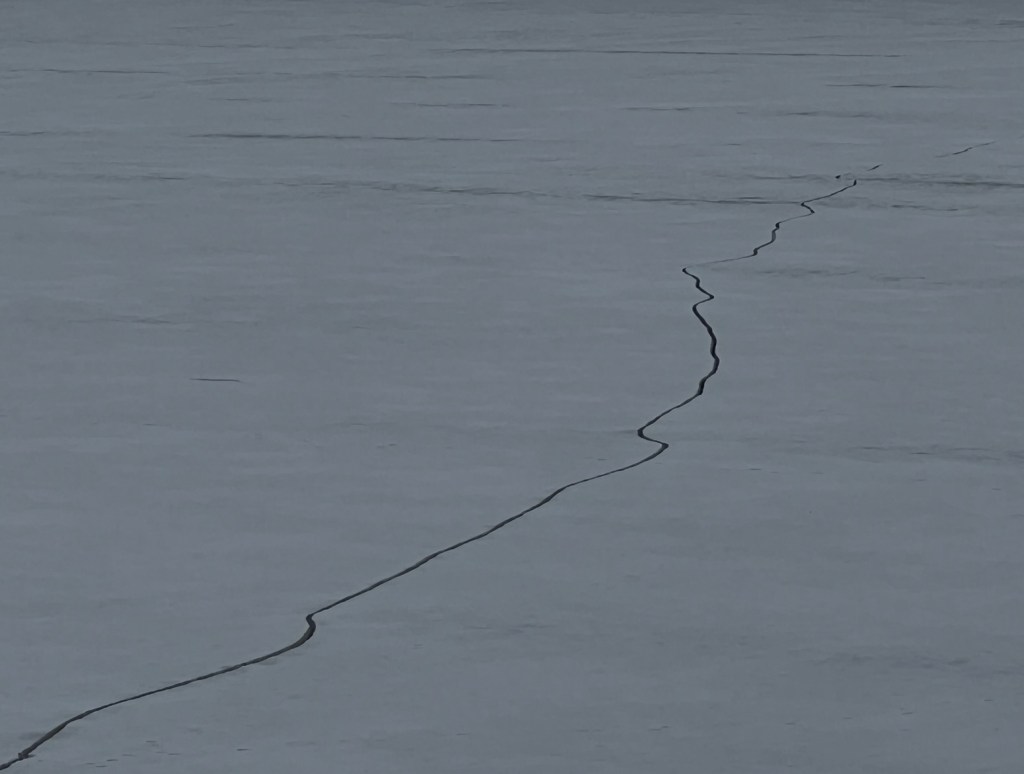

The crevasse in question was substantial. Approximately twenty-five feet wide and sixty feet long. It formed a rippling blue oval that could reasonably conceal our helicopter if we landed inside. The walls converged about twenty feet in the glacier to form a jagged bowl with the basin covered in slabs of broken ice and snow. As we descended at a safe distance, my team observed a hole no more than five feet in diameter offset slightly from the center.

We dismounted the helicopter and approached the side with care. This crevasse hadn’t been seen by the team before, and the bottom being covered in snow and broken ice meant the skier didn’t see it either.

All of us had the same judgement: he rode over and broke through the snow ceiling, carrying enough force to crash through the slab of ice below, creating the hole. My thought, while morbid, was that his ski likely snapped trying to hold his weight as he dangled by his foot.

We didn’t know when he fell or if he was dead or alive, but we knew he was in that hole.

All four of us stood at the edge while our team leader, Buck, squatted at the edge and tightened the bandana around his helmet. He quietly surveyed the bowl below while the rest of us started unpacking some of the medical equipment on our backs. Caitlin, another volunteer like me, started yelling into the crevasse that help has arrived. No response.

“Pulley is almost ready,” Caitlin said to the team.

“Don’t bother,” Buck said. Out of all of us, he had the most experience with rescues. He’d worked as a ranger at Denali for years and recently started working as a trauma surgeon while volunteering for rescues with our team.

“Why?” she said. I turned to face them. Both had pulled off rescues together for years, and I rarely saw them out of sync. The ranger with us continued to prepare for a rope rescue. Buck waved his hand over the crevasse.

“The bottom is delicate. It was thin enough for someone to fall through, including us if we get close to those cracks around the hole. Even if we managed to lower ourselves in, I reckon the rope would get damaged being pulled against the sharp ice. If the weight broke any more of the sides, it’ll send someone swinging. We don’t know how deep it is in there.”

Caitlin looked pensive for a moment and then nodded. The ranger looked up from his work with a confused look on his face. Buck responded.

“I ain’t ruling it out yet, but it’s too risky from where we’re at.”

I decided to speak up.

“What if we got a ladder, laid it across, and descended from a right angle above the hole? It’d be more stable that way.”

Buck turned to me. “You’re getting less dumb by the day, son,” he said with a smile, “but it wouldn’t support the weight. Plus, it’d be too tricky.”

I nodded as Buck turned to the ranger.

“We know who’s in there?”

“A young guy named James Melendez checked in at the ranger station this morning. He was the only person skiing alone today.”

He raised his eyebrows, “When this morning?”

“‘Bout six.”

Buck looked back at the hole and stroked his beard.

“Anything else?”

I ended up interjecting something I heard one of the rangers say before we left for the helicopter.

“Apparently he’s wearing a full red Marlboro ski suit.”

“Shit,” Buck said, “I like him already. Let me tell you what, hand me one of the med kits, a headlamp, and a radio.”

In less than a minute, Buck had tied them all to the end of a rope and started lowering them into the crevasse. We all crouched at the edge as we watched it drop into the inky spot beneath us. Just as it fell in, Buck held the rope tight and raised his radio.

“James, we’re lowering aid to you. Give us a sign of your condition if you can. Stay strong down there. We’ll get you out.”

We heard nothing but the dying echo of Buck’s voice against the mountains. He lowered the supplies further.

“Yell as loud as you can for us, James. We’re close.”

After no response, Buck continued to let out slack and the pack descended further. After some time hearing nothing but the scraping of the rope, our eyes left the crevasse and watched pile of rope behind us. It was a hundred feet long, and it was getting smaller.

“Speak to me, son,” Buck said, quieter this time.

Sixty feet left and the silence continued. The snow felt colder, the mountains grew tighter.

Forty feet, and the ranger turned around. He hung his head and said nothing.

Twenty feet, and Caitlin turned to wave at the helicopter. The engine ripped through the air as Buck extended his arm out into the crevasse, the tip of the rope in his palm.

I looked at him and saw his eyes staring blankly into the wall of ice. Without saying a word, he began pulling the rope back up.

The team was quieter then usual on the ride back, especially me. The others were used to tragedies coming from people not taking the right safety measures. A part of them undoubtedly saw James as a fool, and if I’m being honest, I did too. I just tend to feel more pain for people like them. It wasn’t long ago that I was one of those guys going out alone into the wild. I never made a wrong move, or maybe I just got lucky, but I know now how vulnerable I was.

All I could think about was that guy lying beneath us. I knew with the depth of that chasm he was dead, but I hate that we left him in the dark and in that cold. At least we couldn’t hear anything, I thought to myself. We didn’t hear him suffer. I shuddered and sunk into my seat, watching the mountains get smaller in the window.

Caitlin quickly saw how I was feeling. She put her arm around my shoulder and I felt some of the weight melt away. She worked as a nurse for decades before volunteering and knew how to care for people better than any of us. You could tell by looking at her that the wrinkles on her face were chiseled by years of kindness. Buck, on the other hand, took off his glove and smacked my knee with it. I looked up and saw him smiling, giving me a thumbs up. I smiled too. We often couldn’t communicate easily over the noise of the helicopter, but we always found a way.

We contacted the family members we could at the station but couldn’t do much more. More rangers eventually assessed the situation and determined retrieving the body was too risky. The ice was too fragile but since we knew where James was, we would check the location often and reassess whenever we could. The crevasse stuck out visibly to anyone traveling around it and warnings were issues to all visitors. Little more was disclosed other than informing people that a fatal accident took place there and traveling near it was dangerous. It was marked on our maps and because of the shape the ice took, we took to calling it The Eye from then on.

For almost a month everything went as usual. Over the past season the team started trusting me to address medical issues and I helped bandage an exposed break in a snowboarder’s leg. Being only a high school grad meant I didn’t have a lot of options for learning this stuff, but Caitlin, when she wasn’t volunteering, worked as a biology professor. She encouraged me to sit in on her lectures and it inspired me enroll in community college. I’m planning on applying to med school soon, and keeping at is has made the previous failed rescue attempt less painful. I focused on looking forward.

Leave a comment